II. Donald Judd

Judd’s high-walled bed

Donald Judd — Born in Excelsior Springs, Missouri, 1928. Died in New York City, 1994.

Donald Judd had three main yields: sculpture, writing and furniture. Of course, it is well known that he delved a bit into architecture and was a formidable collector of all manner of things (books, real estate, tartan plaids, etc.), but it is his own texts, designs and dimensional forms that received the full brunt of his passion. It is very hard to simultaneously describe these three aspects, for though each sprang from the same ideological fount, each combination (particular medium with fundamental idea) created quite different results. If we were talking about the sculpture only or the writing only, I don’t think it would be imperative to say much about the remaining two, but the understanding of Judd’s furniture is a more contingent affair; it occupies an almost uncomfortable position between the dogmatic, untenable propositions of his writing and the absolutely transcendent, mind-bending power of his sculpture.

Between the three, the sculptures are most able to bear the load of Judd’s heavy inquiries. They work incredibly well at displaying his fascination with the nature of perception. They’re almost autonomous tools — sculptures independent of the artist, where Judd has set the stage for a deep viewing but left the circuit open, so that it is the viewer and the cosmos that complete it. His writing is a wholly different situation — a primarily closed circuit. The essays are fanatically assertive, all maxim and no poetry; one either gets on board or is quickly ejected. In a very real sense, the furniture is the sculpture with the art removed; it is made of the same materials and employs the same techniques of fabrication, but instead of being finely tuned to challenge the confidence of our senses, a Judd chair is engaged in the physical activity of seated positions. Even though the furniture is actively involved in these physical and practical activities, it has an assertive allegiance to the “right angle” that pushes it a touch closer to the bold tenets of the essays, as both seem to fetishize extremely defined silhouettes — something that the sculptures play with but simultaneously destroy.

Inside Judd’s loft on Spring Street in New York City

An anodized-aluminum desk and chair (left) and bookshelf

So, the furniture is not at all just a weak, watered-down cousin of the sculpture but a unique contribution to the field of furniture design, created by a moiré effect between Judd’s writing and sculpture. To go further, the value or perhaps tone of this furniture, in my opinion, should be termed as something like “speculative design” (possibly an uncomfortable tag for many of the furniture’s admirers). People often confuse what is formally simple with ease-of-use. Judd was adamant about making the distinction that formal simplicity does not equal a lack of complexity, and that simplicity should not be confused with purity. Having majored in philosophy at Columbia University, Judd was not remotely presumptuous and certainly had a manifold outlook. I think the issue of comfort vs. discomfort, which has a blurry existence with that of utility and “good design,” is the central condition in which to consider the furniture. I can speak from experience (an important stance when talking about Judd), having owned two of his chairs, one aluminum and one laminate plywood, that his designs are not primarily comfortable; they work well, but not for lounge-y indeterminate positions. Comfort in furniture is only primary for the dull; this is not to say that furniture should be uncomfortable, just that furniture being the locale of almost all our business (eating, sleeping, fucking, internet exploring, check-writing, etc., etc.), the prime directive should be that it inspire (the journey is the destination or whatever). I would say then that Judd’s furniture seems to be aimed at inspiring a resolute peace of mind before settling in to a particular activity, like, “I will be present for this dinner conversation, or this act of reading, or my forthcoming sleep...”

His pine pieces are perhaps the most rich in aspect of all his furniture, as they seem to meld two separate lineages: the European Arts and Crafts tradition and what might be termed American Pastoral design. Besides being obviously evident in the furniture itself, both influences are easily corroborated by the pieces Judd himself collected. In the many photographs of the interiors of his Marfa, Texas, compound and his NYC home, there are, scattered about: Biedermeier furnishings, pieces by Gerrit Rietveld, Shaker-style desks, works of Rudolf Schindler, Bauhausian tapestries and all manner of handmade objects from both sides of the Atlantic. His high-walled pine bed is an excellent representation of the Judd ideal, as its aim seems to be to block out the noise of the world (literally and figuratively) so that the rich, important activities can be performed with more acuity and calmness of mind.

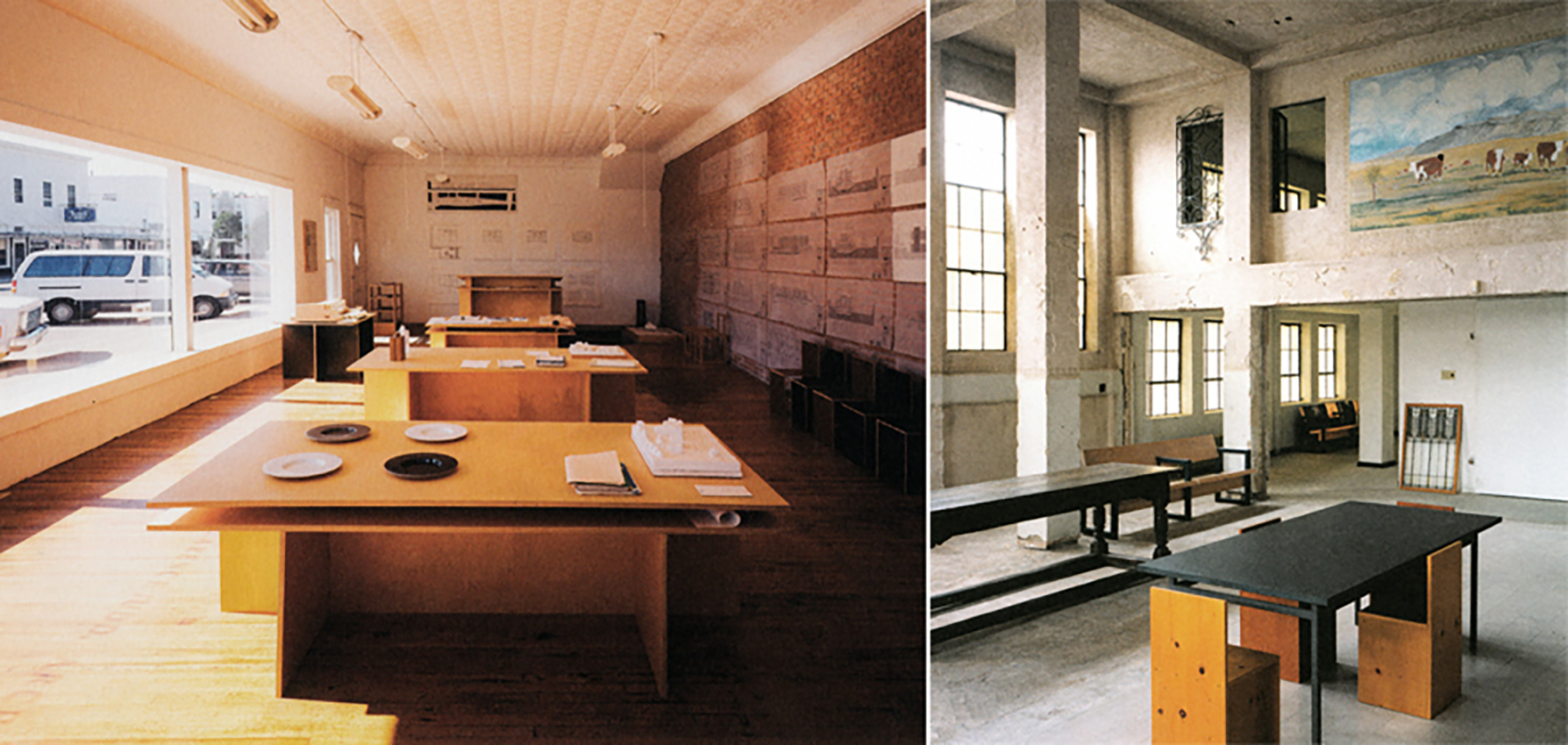

Judd’s architecture office (left) and studio in Marfa, Texas

A Judd desk and chairs

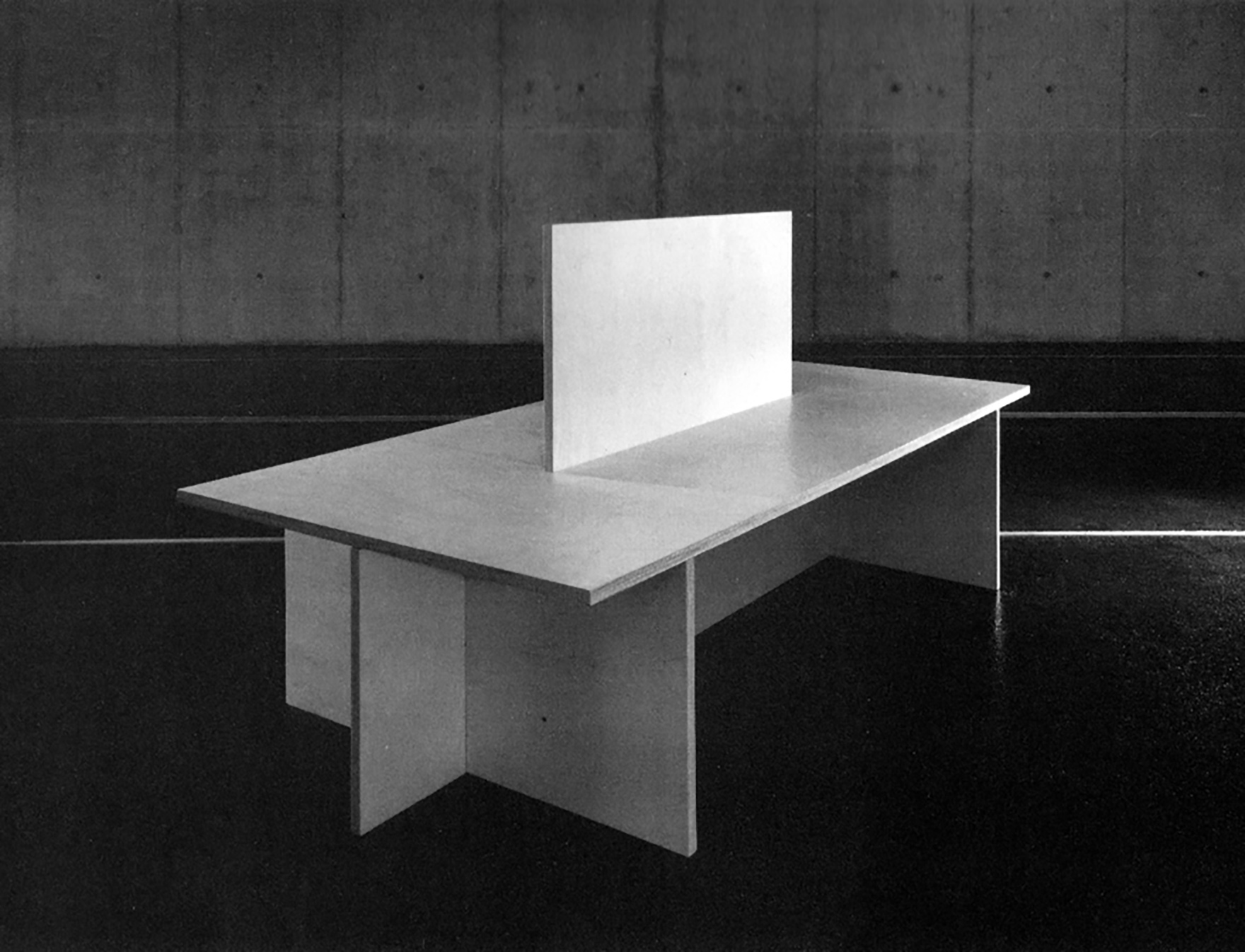

Judd’s standing writing desk

A Judd chair and an interior of the Chinati Foundation in Marfa

A Marfa courtyard with Judd furniture

A Judd desk

Judd’s copper armchair (left) and a stool

Marfa

— AQQ